The Rules We Write By: What the Great Font Debate Can Teach Us About the Risks and Rewards of Defying Convention

Update on Pennsylvania Government Transparency Laws Impacting Agencies and Their Contractors

Court News

Rules Corner

Trivia

The Rules We Write By: What the Great Font Debate Can Teach Us About the Risks and Rewards of Defying Convention

By Spencer R. Short

The Federal Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia, perhaps the second most powerful court in the country, has had it with Garamond. In a March edict that strongly “encouraged” its practitioners to use readable fonts, it singled out Garamond, with its elegant loops and delicate shoulders, for illegibility.

Why Garamond? I should confess that I’ve used Garamond from time to time over the years, taken with what I saw as a kind of typographical alchemy — at once airy and compact, it’s the angel food cake of fonts. But it clearly has its issues. There’s the rococo ornateness of its “section” symbol, for one. Its italics appear oddly irregular. And some have suggested it translates poorly from page to screen, a real problem given the judiciary’s increasing reliance on tablets. These are all reasonable criticisms. Still, for the font’s fans, which include the Department of Justice’s Civil Division apparently, no amount of reason, no matter how iron-clad, could excuse the D.C. Circuit’s preference for "readable" but fusty Times New Roman.

I am a font aficionado but not an expert. It’s a preoccupation that dates to my time studying creative writing in the mid-to-late 1990s, just as standalone word processors were yielding to home computers and the marvels of desktop publishing. For an insecure young poet, access to WordPerfect (yes, I’m that old) and Microsoft Word felt like liberation. From myself, more than anything. Suddenly, I was able to make my poems look like something I’d find in the Paris Review. Or close enough. And so, I cycled through any number of stately serif fonts (Palatino, Georgia, Granjon, Galliard) searching for the right fit. If the perfect typeface couldn’t make my writing better, it at least ensured I didn’t wear callowness on my sleeve.

In other words, I saw fonts as a means of fitting in, a “fake it until you make it” strategy that helped assuage my fear of being unmasked as an imposter — a form of self-help no doubt familiar to litigators who spent their junior associate years mimicking the briefs of better writers. When, much later, I chose Garamond for my briefs, I did so for inverse reasons, an attempt to make my writing stand out rather than fit in. These days, context permitting, I strive for seamless, interconnected writing, with each sentence musically responsive to the one before and paragraphs that flow inexorably from one to the next. Because Garamond is smaller than other fonts, with minimal gradation between thick and thin strokes, I felt like I could fit more words per page and avoid the inky clutter of less elegant fonts. In the aftermath of the D.C. Circuit’s notice, however, the off-hand risk that a judge might find my brief hard to read has given me pause.

* * * *

The D.C. Circuit is not the only judicial voice in the font-recommendation game, of course. Many courts offer advice on formatting, including font choice — though, save for the mono-font U. S. Supreme Court (Century Schoolbook), few impose rigid requirements. For my money, the most interesting discussion of typeface can be found in the Seventh Circuit’s Practitioner’s Handbook, which approaches the subject with an omnivorous, digressive curiosity — it touches on typographical history, anatomy, and aesthetics — that befits the former home of the intellectually-inexhaustible Judge Richard Posner. If you’re not familiar with what “x-height” means to typographers, the Handbook is here to rectify that shortcoming.

Like the D.C. Circuit, the Seventh Circuit’s advice is rooted in “readability.” But its version is less about the mechanical act of reading than what happens next, comprehension. As a result, its Handbook cautions against using Times New Roman:

Typographic decisions should be made for a purpose. The Times of London uses Times New Roman to serve an audience looking for a quick read. Lawyers don’t want their audience to read fast and throw the document away, they want to maximize retention.

When it comes to cognition, the Handbook explains, “[b]riefs are like books rather than newspapers,” and it urges litigators to “read some good books and try to make your briefs more like them.”1 What does this mean in practice? It’s hard to say with any precision. Quantitative analysis and Big Data may be the future of litigation but — for now, at least — the difference between a winning and losing brief remains unavoidably qualitative.

With regard to the fonts themselves, the Handbook’s approach is capacious, embracing any number of typographical deep-cuts and B-sides: New Baskerville, Book Antiqua, Calisto, Century, Century Schoolbook, Bookman Old Style, Baskerville, Bembo, Caslon, Deepdene, Galliard, Jenson, Minion, Palatino, Pontifex, Stone Serif, and Trump Mediäval. Even slab-serif obscurities like Caecilia, Lucida, Officina, Serif, and Rockwell get qualified approval. Really, anything but Times New Roman is fair game. (For those keeping score, the Seventh Circuit also frowns upon, but does not forbid, Garamond. Something about insufficient x-height, it seems. Sorry, DOJ.)

In the end, the split between the two circuits is a bit like one of those law school hypotheticals meant to illustrate the confounding subjectivity lurking beneath every legal rule. We can identify the issue (fonts), the standard (“readability”), and the purpose for the standard (busy judges need accessible briefs) and still get it wrong. Because we sometimes mean different things when we call something readable, what pleases the D.C. Circuit will disappoint the Seventh. If there is any rule applicable to rules, it’s that they’re helpful right up until they aren’t. Rules for fonts, it seems, are no different.

* * * *

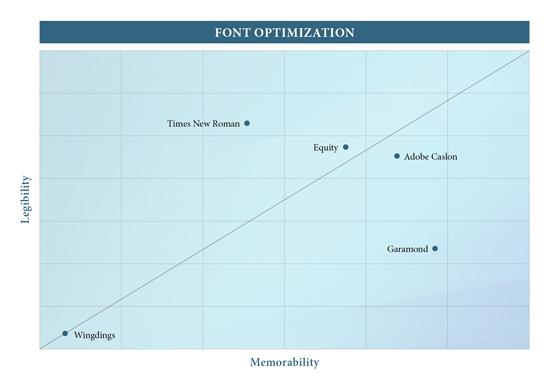

It’s important to recognize that the problems identified by the two circuits are not symmetrical. Legibility is a necessary precondition of memorability; a “memorable” font is worthless if a judge struggles to read it. And yet, the Seventh Circuit’s advice is worth taking to heart. Form is integral to function, and to the extent we want to maximize effectiveness, typeface should be treated not as a passive, interchangeable conveyor of information but as a point of interface that can be optimized for its end-user.

I had largely moved on from Garamond by the time the D.C. Circuit issued its notice. Over the last few years, I’ve experimented with a number of alternatives — Equity, Goudy Old Style, Iowa Old Style, Book Antiqua, Fournier, Adobe Caslon — that captured, in varying degrees, some of Garamond’s elegance and some of Times New Roman’s ease-of-use. In trying to determine the right font for a brief, it is helpful, perhaps, to think of the two circuits as supplying the X- and Y-axes of a scatter plot, with a line of best fit that runs from Wingdings to some yet-undiscovered Platonic ideal:

As someone who has spent a large part of his career challenging pseudoscientific expert testimony, I feel compelled to point out that any placement of fonts within these axes is invariably more art than science. But for litigators navigating hard cases, who recognize the need to maximize the impact of their writing, the nexus between typeface and meaningful, lasting comprehension makes it an art worth exploring.

* * * *

Although every litigator has a story about an opponent whose promiscuous formatting undermined her or his credibility, instances where font choice was, itself, disastrous are few and far between. Still, the D.C. Circuit’s “prohibition” on Garamond provides a helpful reminder that every departure from “convention” carries some risk. A discussion about all of this with a colleague all-too-eager to further an anti-Garamond agenda got me thinking about litigators, the various “rules” we apply to the practice of legal writing, and when, how, and why we apply them.

One of the first things you learn as a writing teacher — I can speak to legal and creative writing, though I imagine it applies elsewhere, too — are the limits of what’s “teachable.” There are rules that can be imposed, and tips and tricks that can be dispensed, that will help a struggling writer be not-bad. Becoming not-bad is sort of like litigators’ Hippocratic oath, the baseline for everything that follows. In keeping with this, law school writing classes correctly focus on easy-to-follow rules and blanket prohibitions, from the architectural heuristic of “IRAC” to stylistic taboos against Selya-isms and “legalese.”

From my experience, this framework doesn’t change a lot for litigators fresh out of law school. When I was a young associate in New York, I was told to imagine our judge on the MTA, with one hand clutching our brief, the other clinging to a strap. This meant short sentences, front-loaded paragraphs, and stripped-down rhetoric. It was solid advice, even if much of our workload at the time was in state courts along the Gulf Coast (and even if the city’s subway cars no longer had straps). After all, a state court judge presiding over motion practice in Jefferson Parish, Louisiana may only have time for a “quick read,” no matter how much she might enjoy the brief equivalent of a leather-bound classic. But it was also good advice for this young attorney, still at the bottom of his learning curve, whose rhetorical tendencies were more Henry James than Hemingway. Rather than maximizing the impact of my writing, my supervising attorney was attempting to minimize the risk posed by my inexperience. I wasn’t being taught to win; I was being taught how not to lose.

Why are these prophylactic rules so valuable? Because we do so much of it, because it becomes almost second nature, it is easy to forget that effective legal writing is, above all else, hard. Every brief is an endless stream of strategic choices. Each word, sentence, phrase, paragraph, etc., constitutes a point of discretion, and each point of discretion is an opportunity for error. Prohibitive rules that eliminate ill-advised options save us from ourselves. As time goes on, as we build experience and skill, the urgency of that advice dissipates. We learn to tailor our approach to each assignment, drafting internal research memos that are substantively and stylistically distinct from discovery motions, dispositive motions, and appeals. In an ideal world, our skills improve in exact proportion to the complexity of our caseload. There comes a point where it’s no longer enough to get out of one’s own way — when winning requires that you be affirmatively good, i.e., distinctive, memorable, compelling. It can be a frustrating process. It’s not just that being not-bad is different from being good, though it is. It’s also the fact that becoming good is elusive and incremental, the slow-cooked product of time, repetition, diligence, and probably (painful as it may be to admit) some degree of natural talent.

* * * *

If this distinction can be hard to recognize in real-time, the diminishing returns of an overly programmatic approach are nonetheless right there in the Seventh Circuit’s Handbook. As measured by “maximizing retention,” good brief writing requires “a different approach,” utilizing “different typefaces” and “different column widths” and, most importantly, adopting “different writing conventions.” This can mean a lot of things, of course, from varying tone, to alternating sentence length, to rhetorical, and structural re-mixing, to, yes, the occasional joke or literary reference.

Still, there’s a timeworn axiom in creative writing workshops that certain gestures have to be “earned,” by which we mean that risk requires correlative attention to all the “little things” that engender trust in a reader. If this ultimately begins to feel somewhat meaningless in the context of poetry, I think it remains a helpful mindset when it comes to drafting briefs. When we fail to “earn” our departures from convention, we risk calling attention to our deficiencies; when we take unadvisable risks, it is our clients who pay the price. Litigators tend to be risk-averse for a reason.

So how do we know when we’ve earned the right to depart from convention? Like many young associates, I sometimes confused distinctive style for quality writing. But I was lucky. I spent the first few years of my career apprenticed to excellent writers, drafting and re-drafting briefs. And, although I rarely had the final word, the redlines fed back to me were revelatory. By paying close attention to what got cut (stylistic flourishes, invariably), sharpened, and rearranged, I slowly began to grasp the delicate balance between what’s essential, what’s prohibited, and what’s distinctive. As time went on, the redlines became less red. Occasionally, even my “flourishes” survived the bloodshed.

Not everyone has the luxury of such careful oversight. And the only alternative — self-knowledge — can be hard-won. The French moral philosopher Albert Camus once described “genius” as “intelligence that knows its frontiers,”2 and it’s a definition I find particularly useful when it comes to litigating. Although we strive to know all we can about every case, certainty remains elusive. The law, the court, the judge, and our clients each represent “frontiers” of resistance to the kind of totalizing knowledge and awareness we crave. The best (perhaps only) way of dealing with this uncertainty is an unblinking, even ruthless, self-awareness. When it comes to effective brief writing, no amount of skill or strength can overcome blindness to our own limitations.

__________________

1 Seventh Circuit Practitioner’s Handbook for Appeals, at p. 173-74 (found at: http://www.ca7.uscourts.gov/rules-procedures//Handbook.pdf)

2 Albert Camus, The Myth of Sisyphus, pg. 70 (Knopf 1983).

Update on Pennsylvania Government Transparency Laws Impacting Agencies and Their Contractors

By Karl S. Myers

Pennsylvania state and local government agencies and their contractors should beware of two recent developments of note in Pennsylvania public transparency law.

Government agency consultants are not “internal” parts of the agency.

First, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court has decided that outside consultants working for government agencies are not treated as part of the agency under the internal, pre-decisional deliberations exception to public records disclosure in the Right-to-Know Law (RTKL) – Pennsylvania’s iteration of the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA). That exemption enables an agency employee to freely share his or her views on an issue to be decided by an agency without fear that someone might be looking over his or her shoulder. Put another way, this RTKL exemption prevents government from operating in a fishbowl – with every move watched by onlookers.

But what happens when the agency hires outside consultants, financial advisors, and lawyers? In Chester Water Authority v. Pennsylvania Department of Community & Economic Development, 249 A.3d 1106 (Pa. 2021), a Commonwealth agency hired a consulting firm to serve as a city’s economic recovery coordinator. The firm, in turn, hired financial services and law firms as subcontractors. A RTKL requester asked for copies of communications among the agency, consultant, financial services firm, and law firm. The court held the internal, pre-decisional deliberations exemption shielded none of the communications. It reasoned that the consultants and firms were not “internal” parts of the agency under the plain language of the RTKL.

The lesson of Chester Water Authority for agencies and contractors is to be mindful and careful, as the RTKL does not automatically protect all communications between them. It is true that other RTKL exceptions may apply to protect these materials from disclosure, and the attorney-client privilege separately protects an agency’s communications with its outside counsel. But the court’s decision still shows that agencies and their consultants must not assume that outside consultants will be treated as components or arms of an agency under the RTKL.

Agencies must publicly post their meeting agendas in advance.

The second recent transparency development is Gov. Tom Wolf’s signing into law of a rare change to the Pennsylvania Sunshine Act on June 30, 2021. For many years, the Act has required agencies to publish the date, time, and place of their meetings. Act 65 of 2021 (formerly Senate Bill 554), passed unanimously by the Senate and House, adds a new requirement – agencies also must post their meeting agendas on their websites and at their offices and meeting locations at least 24 hours before each meeting and provide agenda copies to meeting attendees. This change ensures the public is aware of the agency’s planned business at each meeting – not just its date, time, and place. Anything not on the agenda cannot be the subject of official agency action, with three exceptions: (1) emergency issues; (2) new matters first arising within 24 hours before the meeting’s start; and (3) new issues arising during the meeting. Act 65 takes effect on Aug. 29, 2021.

Court News

In the May 18, 2021 primary, voters chose the candidates for the four vacancies on Pennsylvania’s appellate courts:

In the May 18, 2021 primary, voters chose the candidates for the four vacancies on Pennsylvania’s appellate courts:

- For the one open Supreme Court seat, the candidates are Commonwealth Court President Judge Kevin Brobson and Superior Court Judge Maria McLaughlin;

- For the one open Superior Court seat, the candidates are Philadelphia Judge Timika Lane and Megan Sullivan; and

- For the two open Commonwealth Court seats, the candidates are Commonwealth Court Judge Drew Crompton, Stacy Wallace, Philadelphia Judge Lori Dumas, and Allegheny County Judge David Spurgeon.

The general election for these appellate court seats is set for Nov. 2, 2021.

As of this writing, there are no open seats on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit, so there are no vacancies for the President to fill on that court.

Rules Corner

The Pennsylvania Superior Court recently clarified when parties challenging discovery requests may take collateral order appeals in the context of trial court orders for in camera review. In Fisher v. Erie Insurance, No. 1597 WDA 2018 (Pa. Super. June 25, 2021), the court quashed an immediate appeal from a trial court’s order directing in camera review of requested materials. The court clarified that a later order directing production after review might be immediately appealable under the collateral order doctrine. The court also went out of its way to specifically disapprove of a trial court’s direct production of materials following in camera review, given it might deprive a party still claiming protection of its ability to appeal the production order.

The Pennsylvania Superior Court recently clarified when parties challenging discovery requests may take collateral order appeals in the context of trial court orders for in camera review. In Fisher v. Erie Insurance, No. 1597 WDA 2018 (Pa. Super. June 25, 2021), the court quashed an immediate appeal from a trial court’s order directing in camera review of requested materials. The court clarified that a later order directing production after review might be immediately appealable under the collateral order doctrine. The court also went out of its way to specifically disapprove of a trial court’s direct production of materials following in camera review, given it might deprive a party still claiming protection of its ability to appeal the production order.

The Pennsylvania Supreme Court has elaborated on the Walker rule. Under that rule, a separate notice of appeal is generally required to appeal an adverse ruling on each trial court docket – even when a trial court issues a single order covering multiple case dockets. In Always Busy Consulting v. Babford & Co., 247 A.3d 1033 (Pa. 2021), the court clarified that the Walker rule does not apply – and thus an appellant can file a single notice of appeal – when a trial court issues one order on the lead docket number in consolidated civil cases involving the same parties, claims, and issues, and where all record information necessary to decide the case is filed on the lead docket.

The U.S. Supreme Court recently curbed the power of federal district courts to alter prior awards of appellate costs. In City of San Antonio v. Hotels.com, 141 S. Ct. 1628 (2021), online travel companies prevailed in the court of appeals in their challenge to a $55 million jury award for alleged underpayment of hotel taxes. The court of appeals awarded the companies the costs a prevailing party typically receives on appeal – filing fees, transcript costs, and other items (but not including attorneys’ fees) – under Federal Rule of Appellate Procedure 39. On remand, the companies asked the district court to add to that award $2.2 million in premiums for appeal bonds (also known as supersedeas bonds) they had to buy to secure the judgment. The district court found it was required to add that amount to the cost award, as the court of appeals had awarded costs. The Supreme Court agreed, holding that Rule 39 gives a court of appeals the discretion to award costs and that a district court cannot alter the appeals court’s discretionary allocation later on.

Trivia

Contrary to what some may believe, the U.S. Supreme Court is not the oldest appellate court in the nation. And there is an ongoing dispute over which state’s highest court is the oldest. For instance, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court claims it is the “oldest appellate court in the nation” because its history traces to the Provincial Court, established in 1684. But the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court seems to disagree, arguing it “is the oldest appellate court in continuous existence in the Western Hemisphere,” as it was originally known as the Superior Court of Judicature, established in 1692. While Pennsylvania appears to have edged Massachusetts out by eight years, some still quibble over the details. Perhaps that’s to be expected – we are lawyers, after all.

Contrary to what some may believe, the U.S. Supreme Court is not the oldest appellate court in the nation. And there is an ongoing dispute over which state’s highest court is the oldest. For instance, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court claims it is the “oldest appellate court in the nation” because its history traces to the Provincial Court, established in 1684. But the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court seems to disagree, arguing it “is the oldest appellate court in continuous existence in the Western Hemisphere,” as it was originally known as the Superior Court of Judicature, established in 1692. While Pennsylvania appears to have edged Massachusetts out by eight years, some still quibble over the details. Perhaps that’s to be expected – we are lawyers, after all.

Information contained in this publication should not be construed as legal advice or opinion or as a substitute for the advice of counsel. The articles by these authors may have first appeared in other publications. The content provided is for educational and informational purposes for the use of clients and others who may be interested in the subject matter. We recommend that readers seek specific advice from counsel about particular matters of interest.

Copyright © 2021 Stradley Ronon Stevens & Young, LLP. All rights reserved.